Michael Jackson, Otherness & Diversity

During his lifetime and even in his death, Michael Jackson has been accused of voluntarily erasing his black features in an attempt at “becoming white”, and therefore gaining access to the exclusive world of the dominating elite.

His critics paint him out to be nothing short of a bigot, someone whose admiration for the standards of white America made him not only alter his own appearance but also see the world through these lenses. But is it possible that the man who wrote the diversity anthem Black or White was, in fact, a bigot?

In a previous thread (see below) we spoke about Michael’s race/ethnicity and how it was impossible for him to ever cease being black, shedding light on his internal perceptions of himself and his community. https://twitter.com/manuelabezamat/status/1186598490178240512?s=20

In this thread, which complements the other, we’ll focus on the outside world, on how Michael perceived other cultures – in summary, how he saw difference, proving that his personality and his beliefs are the opposite of what’s expected from a prejudiced and intolerant person.

Before we dig into Michael’s relationship with other cultures/ethnicities, let’s take a quick look at some concepts that will be used in this thread, and that belong to the field of Anthropology: Otherness, Ethnocentrism and Cultural Relativism. When interacting with people from other ethnicities/cultures we’re faced with Otherness, defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary as “the quality or state of being other or different”. In such situations, it becomes clear that our cultural habits and beliefs aren’t universal.

Some see these encounters as an opportunity to learn, while others respond by judging people by the social/cultural standards of their own group, believing them to be superior. These people incur in Ethnocentrism (‘ethnos’ – nation, cultural group; ‘centric’ – center).

German anthropologist Franz Boas was one of the pioneers in fighting Ethnocentrism in his field. Going against the main anthropological current, which placed each culture in an evolutionary scale, he instead vouched for them to be analyzed within their own cultural standards.

Boas’ theory, called Cultural Relativism, was a product of his intense fieldwork in the late 19th century. Living with the Inuits of Baffin Island, he concluded that learning their habits/language was essential to understanding them and denaturalizing his own cultural standards.

Polish-born anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski took the debate further. Spending years among the natives of the Trobriand Islands, he concluded that fieldwork was essential to grasp “the native’s point of view, (…) to realize his vision of his world”.

Even though Boas’ and Malinowski’s works are complex, their message is simple – it’s only by having continuous/frequent contact with Otherness that we avoid the pitfalls of Ethnocentrism and realize that we’re all ethnic beings, none better than the other.

You may ask what any of this has to do with Michael Jackson. The answer is – everything.

Michael Jackson was naturally empathic. His understanding and concern about others were summarized by an old proverb he often recited: “don’t judge a man until you’ve walked two moons in his moccasins”.

His natural empathy was only matched by his intellectual curiosity. Bob Sanger, his longtime lawyer, said that his personal library had 10,000 books and that they’d often talk about “psychology, Freud and Jung, (…) black history and sociology dealing with race issues.”

Michael also travelled from an early age for work, both inside and outside of the US. His tours allowed him to visit dozens of countries around the world – from China to Brazil, not to mention his personal trips, like the ones he took to Africa.

His sense of empathy, his intellectual curiosity and his travels, when combined, gave Michael a rare perspective, one that can be found in trained anthropologists – that humankind is comprised of a myriad of ethnicities/cultures that should be appreciated in their uniqueness.

Michael took it even further – he discovered that Otherness and diversity aren’t, as some would think, a source of weakness or conflict, but a source of strength and unity. From Otherness comes Oneness, a point of view that he expressed in his music and his humanitarian work.

In a 1979 interview to Jet Magazine, he stated: “I’m really not a prejudiced person at all (…) if you look at the many wonders inside the human bodies—the different colors of organs…and all these colors do different things in the human body – why can’t we do it as people?”

The following year, Michael and Jackie Jackson co-wrote a song called “Can You Feel It”, the third single out of the Jacksons’ album Triumph (1980). The song speaks about unity and the world coming together.

The lyrics are poignant: “All the colors of the world should be lovin’ each other wholeheartedly (…)”; “Spread the word and try to teach the man who’s hating his brother, when hate won’t do, when we’re all the same, ’cause the blood inside me is inside you.”

In late 1980, Michael had the idea of making a film out of the song. The result was “The Triumph”, a 9 min+ visual masterpiece starring the Jackson brothers in outer space, delivering a message of love to people of multiple ethnic backgrounds.

Two moments in the film stand out. First, the prelude, composed by Michael, which speaks about the “beginning”, where “men and women of every color and shape (…) would ignore the beauty in each other”, but “never lose sight of the dream of a better world, that they could unite.”

Later, people of all ethnicities are shown staring at a black hole, where a single peacock feather appears. A native-American man emerges from the crowd and an African-American boy holds his hand. Soon everyone else does the same, and the single feather turns into a full plumage.

The highly symbolic nature of this film can’t be ignored. In the peacock feather scene, the message is clear – while one feather/culture is beautiful by itself, it’s only when all feathers/cultures join together that the full beauty is unleashed. From Otherness comes Oneness.

The idea of Oneness shows up again in the 1985 charitable global hit “We are the World”, co-written by Michael and Lionel Richie. The song, which speaks about the world coming together for a good cause, managed to raise roughly $ 60 million for the famine in Ethiopia.

Captain EO, a 17+ min 3D film made for Disney that came out in 1986, had Michael play the part of an intergalactic captain on a mission to save a planet from the ruling of its evil queen, played by Anjelica Houston.

The two songs featured in the film, “We Are Here to Change the World” and “Another Part of Me” have EO bring the message of a new era, where love and unity overcome fear and hate.

In “Another Part of Me”, which later featured in Michael’s 1987 Bad album, the lyrics follow the pattern of “Can You Feel It” – “The planets are linin’ up, we’re bringin’ brighter days. They’re all in line waitin’ for you, can’t you see? You’re just another part of me.”

Even if his previous work referenced diversity, the Dangerous album (1991) and its short films took Michael’s relationship with other cultures to a new level. It was then that his message about diversity became louder and more explicit than ever.

The first track, “Jam”, sets the tone for the album by bringing up Oneness again – “Nation to nation all the world must come together, face the problems that we see then maybe somehow we can work it out”. From Otherness comes Oneness.

“Heal the World”, the timeless humanitarian song that prompted many to look more kindly upon their neighbor for the first time, is fascinating in that it combines three elements that summarize Michael’s worldview: humanitarian work, diversity and children.

The Heal the World short film illustrates this by showing children from all over the world in distress. The message is clear – the children of the world shouldn’t have to suffer.

Michael took action by creating the Heal the World Foundation in 1992. In a HTW press conference, he announced the donation of tons of supplies to war-torn Sarajevo and actions aimed at inner-city children, also speaking against prejudice and ethnic hatred.

The 1993 Super Bowl halftime show included what was possibly his most touching performance of “Heal the World”. The segment starts with the audience performing a card stunt, which creates the image of children of different ethnicities to the sound of “We Are the World”.

Then, as “Heal the World” starts playing, Michael is joined onstage by people from various cultures – many dressed in traditional garments – who sing together and hold hands as a balloon in the shape of planet Earth is inflated at center stage.

The intersection of children and diversity would provide a lifelong fascination for Michael. In a 2003 documentary, he mentioned that he considered adopting two children from each continent, and one of his most prized personal possessions was this painting below.

In all of Michael Jackson’s body of work there’s one song and accompanying short film that are considered not only the summary of his thoughts on race, Otherness and diversity, but one of the landmarks of pop culture: the unmistakable “Black or White”.

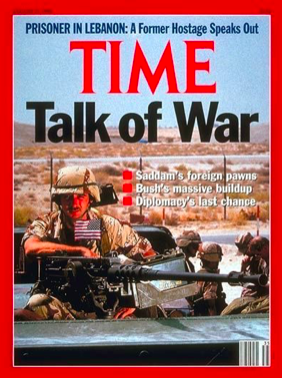

The first single out of Dangerous, “Black or White” was released in November 11, 1991, a turbulent year in terms of world history. That was the year that the Soviet Union collapsed, the Gulf war ended and the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia intensified.

In this scenario of hopelessness and change, a young black entertainer brought about a message of hope and positivity, shifting the focus from the flaws of humanity to its beauty and ingenuity.

“Black or White” stayed at number 1 in the Billboard Hot 100 for 7 weeks, also reaching the top of the charts in various other countries around the world. The B or W short film debuted simultaneously in 27 countries on November 14, to an estimated audience of 500 million people.

The B or W short film is at times symbolic and at other times explicit in its message. Michael and Vincent Patterson, his choreographer, had conceived it as a narrative in which the singer would visit different cultural settings around the world.

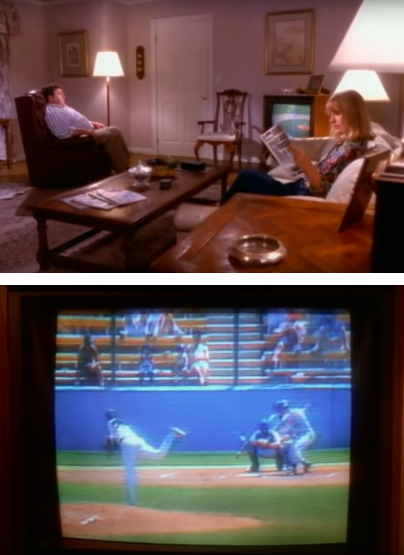

The film starts by showing a typical middle-class household in suburban USA. In the living room, dad watches sports on TV while mom reads a tabloid newspaper. They represent the intellectually divested/short-sighted mainstream society, which is blind in its Ethnocentrism.

In true Michael Jackson fashion – the singer saw children as the bearers of endless curiosity, while also lacking the prejudices and restraints of the adults – it’s up to their son, played by Macaulay Culkin, to open their eyes to a world filled with endless possibilities.

The power of the son’s message literally blows dad through the roof, landing him in a different reality, where people have different ways of life. He’s then introduced to a new character, Michael Jackson, who’s taking part in a dance ritual with native Africans.

From that point forward, Michael, like an anthropologist, becomes an interpreter of cultures, seamlessly travelling from one to the other while either taking part in their dance or dancing to his own rhythm.

The sequence where he goes from dancing with the African natives to dancing in a studio with the traditional Thai dancers and then “breaking free” from the studio setting to join the Native-Americans in a ritual in the desert is particularly poignant.

In the making of B or W, Michael was unhappy with John Landis’ original idea of just having him dance in front of a gray background. He understood the symbolic importance of interacting with other cultures, and that by joining them, he showed that they were different, but equal.

The scene of Michael with the Native-Americans has the natives wearing traditional garments and includes the original sounds of their chants. The power and the beauty of this culture can be felt as everyone’s surrounded by men storming in, riding horses – not a cowboy in sight.

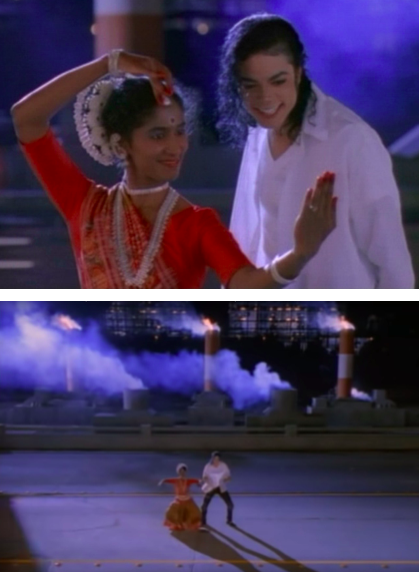

From the desert we’re taken to an urban environment, where Michael interacts with an Indian native. What jumps out in this scene is the contrast between the “exoticness” and warmth of the woman and the soullessness of the industrial background.

Two issues arise from this scene. 1) The meaning of “exoticness”, this ethnocentric category that stigmatizes Otherness 2) The erasure of traditional cultures by our capitalist society. By joining the dancer, Michael picks the side of diversity and understanding.

Travelling to Russia, Michael joins dancers in front of Saint Basil’s Cathedral, evoking feelings of brotherhood. The scene morphs into a glass globe, which is picked up by a white baby, sitting next to a black baby on top of planet Earth, suggesting a future of racial harmony.

The next scene, the most racially-charged of them all, has Michael defiantly singing “I ain’t scared of your brother, I ain’t scared of no sheets, I ain’t scared of nobody, girl, when the going gets mean” to bigots and racists, against footage of a burning cross.

From there we’re taken to the inner city, where Michael is seen among children of different ethnicities – the new generation – singing powerful lyrics “it’s not about races, just places, faces (…) I’m not going to spend my life being a color.”

The next scene shows Michael atop the Statue of Liberty. As the camera zooms out, he’s surrounded by monuments from all over the world. It becomes clear that, while he sees the world from the viewpoint of his culture, he considers other cultures to be equal to his.

The end of the short film brings the iconic (then ground-breaking) morphing segment, where men and women of various ethnic backgrounds merge faces while singing repeatedly “it’s black, it’s white, it’s tough for you to get by.”

The Black or White short film hit the world like a ton of bricks. People of every culture were mesmerized with what they’d seen – the biggest star in the planet showing, through astonishing visual effects, that he appreciated their way of life, and that it’s okay to be different.

In the following years, the Dangerous and HIStory tours took the singer to countless cities in Europe, Asia and South America, helping cement his vocation as a spokesman for world cultures. Even those that didn’t speak English felt like they could relate to the man and his music.

Michael Jackson’s message of tolerance, diversity and racial/cultural harmony helped shape the minds of generations of people around the world, that would continue to spread his values from that point forward. The singer had reached his goal: from Otherness came Oneness. //

SOURCES:

LECOCQ, Richard (@richardjllecocq)

ALLARD, François “Michael Jackson: All the Songs – The Story Behind Every Track”

SMALLCOMBE, Mike (@mikesmallcombe1) “Making Michael: Inside the Career of Michael Jackson”

ROBERTS, Randall “Michael Jackson’s lawyer, Bob Sanger, talks to West Coast Sound about the pop star, his life and his reading habits” (LA Weekly)

KELLOGG, Carolyn “Michael Jackson, the bookworm” (Los Angeles Times)

HIRSHEY, Gerri “Michael Jackson: life as a man in the magical kingdom” (Rolling Stone) “Jackson interview seen by 14m” (BBC News)

FAILES, Ian “An oral history of morphing in Michael Jackson’s ‘Black or White’” (Cartoon Brew)

Michael Jackson official website

Oregon State University’s Anthropological Glossary

KING, Charles “ Genius at work: how Franz Boas created the field of Cultural

Anthropology” (Columbia Magazine)

“Bronislaw Malinowski – LSE pioneer of social anthropology” (LSE website)

Discover Anthropology website; the works of Franz Boas and Bronislaw Malinowski.

Great post. MJ was always about love and unity.

You wrote: “The sequence where he goes from dancing with the African natives to dancing in a studio with the traditional Thai dancers and then “breaking free” from the studio setting to join the Native-Americans in a ritual in the desert is particularly poignant.” What do you mean by MJ “breaking free” from the studio to join a dance in the desert? Why did you call it “breaking free”? Wasn’t it just a video of transitioning from scene to scene?

Also, haven’t you noticed the ad libs MJ sang at the very end of the song “Black or White”, where he says “It’s tough for you to get by”? What did he mean by “It’s tough for you to get by”?

Thank you.

LikeLike

Hello Kate,

I used the expression “breaking free” to speak of what I see as a double metaphor in that transition scene: 1) the studio walls representing the confinement of the cultural/social standards of Michael’s own culture, that limits his worldview, and that he breaks free from by “tearing them down” and joining people from another culture in a ritual; 2) the conflict between intelectual/theorical knowledge of other cultures versus practical/real-life coexistence with people from different cultures. The latter is often brought up in the anthropological field, and Boas, who, as I wrote, was one of the pioneers in fieldwork, often criticized “chamber ethnologists”, who created their theories based on second-hand evidence instead of having actual contact with other cultures. It’s very telling that Michael chose to show the studio walls being torn down.

Regarding the ad-libs “It’s tough for you to get by”, I believe he meant that it’s tough going through life dealing with racism and bigotry.

LikeLike

I do agree that the ad-libs “It’s tough for you to get by” was in regards to it being tough going through life dealing with racism and bigotry. That’s exactly what I thought it meant.

You said: “I see (“breaking free”) as a double metaphor in that transition scene: 1) the studio walls representing the confinement of the cultural/social standards of Michael’s own culture, that limits his worldview, and that he breaks free from by “tearing them down” and joining people from another culture in a ritual; 2) the conflict between intellectual/theoretical knowledge of other cultures versus practical/real-life coexistence with people from different cultures.”, but MJ was black with black culture, not Asian with Asian culture, so why would MJ see Asian culture, with him in the studio, as breaking free from his own culture?

And isn’t Asian culture another culture different from his own just as Native American culture is different from his own? So why would he break free from the studio walls with Asians into a ritual with Native Americans as a different culture his going into?

Also, when you stated: “The sequence where he goes from dancing with the African natives to dancing in a studio with the traditional Thai dancers and then “breaking free” from the studio setting to join the Native-Americans in a ritual in the desert is particularly poignant.”, were you referring to MJ “breaking free” from the African culture as well?

Thank you.

LikeLike